Pre-State Israel:

The Balfour Declaration

(November 1917)

Pre-State Israel: Table of Contents | Sykes-Picot Agreement | British Mandate

Reference

- Declaration Text

- Commentary on Declaration

- Declaration's Secret Jewish Author

- British Government Anti-Semitism

Official Endorsements

- Arab Leader Emir Faisal (1919)

- U.S. Congress (1922)

- U.S. President Hoover (1932)

- U.S. President Roosevelt (1937)

Important Figures

Balfour Declaration:

Text of the Declaration

(November 2, 1917)

Balfour Declaration: Table of Contents | Commentary | Congressional Endorsement

The British government decided to endorse the establishment of a Jewish home in Palestine. After discussions within the cabinet and consultations with Jewish leaders, the decision was made public in a letter from British Foreign Secretary Lord Arthur James Balfour to Lord Rothschild. The contents of this letter became known as the Balfour Declaration.

Foreign Office

November 2nd, 1917Dear Lord Rothschild,I have much pleasure in conveying to you. on behalf of His Majesty's Government, the following declaration of sympathy with Jewish Zionist aspirations which has been submitted to, and approved by, the CabinetHis Majesty's Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavors to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.I should be grateful if you would bring this declaration to the knowledge of the Zionist Federation.Yours,Arthur James Balfour

Sources: UNISPAL

Balfour Declaration:

Balfour Declaration:

Secret Jew Drafted Balfour Declaration

Balfour Declaration: Table of Contents | Declaration Text | Arthur Balfour

The author of the Balfour Declaration, Leopold Amery, is Jewish, according to Professor Rubenstein of modern history at the University of Wales. As the assistant secretary to the British war cabinet in 1917, Amery also helped to create theJewish Legion. The Legion became the first organized Jewish fighting force since Roman times, and the precursor to the Israeli Defense Force (IDF).

Amery's 1955 autobiography merely mentions his mother, whom he said was on of the many Hungarian exiles fleeing Constantinople. He writes that his father is from an old English family.

Rubinstein's research revealed that Amery's mother was named Elisabeth Joanna Saphir, and the family lived in Pest, which later became Budapest, and the city's first Jewish quarter. He also found that her parents were both Jewish, and that Amery changed his middle name from Moritz to Maurice. This helped him disguise his identity.

Amery's sons took two very different paths in their acknowledgment of their heritage. John joined the side of the Nazisduring World War II and was later hanged for treason. Julian became a member of Parliament and a solid supporter of the Jewish state.

Rubenstein has several theories as to why Amery hid his identity. Among them are a genuine fear of persecution, confusion as to his own personal faith after the conversion of his relatives to Protestantism, and possible roadblocks for his future political career. Additionally, he may not have wanted the Jewish community to pressure him for political favors.

Sources: Davis Douglas, "Balfour Declaration's author was a secret Jew," The Jerusalem Post. (January 12, 1999)

Arthur Balfour

(1848 - 1930)

Arthur Balfour was born on the family's Scottish estate in East Lothian in 1848. Educated at Eton and Trinity College, Cambridge, he entered the House of Commons in 1874 as the Conservative MP for Hertford.

In 1878 Balfour became private secretary to his uncle, the Marquess of Salisbury, who was Foreign Secretary in the Conservative government headed by Benjamin Disraeli.

In the 1885 General Election Balfour was elected to represent the East Manchester constituency. The Marquess of Salisbury, who was now Prime Minister, appointed him as his Secretary for Scotland. Other posts during the next few years included Chief Secretary of Ireland (1887), First Lord of the Treasury (1892) and leader of the House of Commons (1892).

Balfour replaced his uncle as Prime Minister in 1902. The most important events during his premiership included the 1902 Education Act and the ending of the Boer War. The topic of Tariff Reform split Balfour's government and when he resigned in 1905, Edward VII invited Henry Campbell-Bannerman to form a government. Campbell-Bannerman accepted and in the 1906 General Election that followed the Liberal Party had a landslide victory.

Balfour remained leader of the Conservative Party until he was replaced by Andrew Bonar Law in 1911. He returned to government when in 1915 Herbert Asquith offered him the post of First Lord of the Admiralty in Britain's First World War coalition government. The following year, David Lloyd George, the new Prime Minister, appointed him as Foreign Secretary, and consequently was responsible for the Balfour Declaration in 1917 which promised Zionists a national home in Palestine.

Balfour left Lloyd George's government in 1919 but returned to office when he served as Lord President of the Council (1925-29) in theConservative government headed by Stanley Baldwin. Arthur Balfour died in 1930.

Sources: Spartacus Educational

Leopold Amery

(1873 - 1955)

Leopold Amery was born in Gorakhpur, India, on November 22, 1873. Educated at Harrow and Balliol College, Oxford, he worked as chief correspondent for The Times during the Boer War. He also edited seven volume, The Times History of the South African War (1900-09).

A member of the Conservative Party, in 1911 Amery was elected to represent Sparkbrook, Birmingham, in the House of Commons. Amery, who recent research has revealed was Jewish, wrote the Balfour Declaration. As the assistant secretary to the British war cabinet in 1917, Amery also helped to create the Jewish Legion.

In the government headed by David Lloyd George, he served as under-secretary of state for the colonies (1919-21). This was followed by the post of First Lord of the Admiralty (1922-24) and then colonial secretary (1924-29).

Amery lost office when Ramsay MacDonald and the Labour Party formed the government in 1929. He remained out of office throughout the 1930s and emerged as one of the party's leading critics of the government's appeasement policy.

In 1940, Neville Chamberlain appointed Amery as secretary of state for India and Burma. His son, John Amery, made pro-Nazi broadcasts during the Second World War. He also made speeches in favor of Adolf Hitler in occupied Europe and after the war was executed for high treason.

After his retirement from politics Amery published his autobiography, My Political Life (1955). Leopold Amery died in London on September 16, 1955.

Sources: Spartacus Educational

Balfour Declaration:

Commentary on the Declaration

Balfour Declaration: Table of Contents | Text of Declaration | Congressional Endorsement

On November 2, 1917, Britain issued the Balfour Declaration:

His Majesty's Government views with favor the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavors to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.

According to the Peel Commission, appointed by the British Government to investigate the cause of the 1936 Arab riots, "the field in which the Jewish National Home was to be established was understood, at the time of the Balfour Declaration, to be the whole of historic Palestine, including Transjordan."

The Mandate for Palestine's purpose was to put into effect the Balfour Declaration. It specifically referred to "the historical connections of the Jewish people with Palestine" and to the moral validity of "reconstituting their National Home in that country." The term "reconstituting" shows recognition of the fact that Palestine had been the Jews' home. Furthermore, the British were instructed to "use their best endeavors to facilitate" Jewish immigration, to encourage settlement on the land and to "secure" the Jewish National Home. The word "Arab" does not appear in the Mandatory award.

The Mandate was formalized by the 52 governments at the League of Nations on July 24, 1922.

Balfour Declaration:

Balfour Declaration:

Balfour Declaration:

Emir Faisal Endorses Declaration

Balfour Declaration: Table of Contents | Text of Declaration | Congressional Endorsement

Chaim Weizmann, wearing headscarf at left as a sign of respect, meets with Emir Faisal (circa 1919) |

Emir Faisal, son of Sherif Hussein, the leader of the Arab revolt against the Turks, signed an agreement with Chaim Weizmann and other Zionistleaders during the 1919 Paris Peace Conference. “Mindful of the racial kinship and ancient bonds existing between the Arabs and the Jewish people,” it said, “and realizing that the surest means of working out the consummation of their national aspirations s through the closest possible collaboration in the development of the Arab states and Palestine.” Furthermore, the agreement looked to the fulfillment of the Balfour Declaration and called for all necessary measures “...to encourage and stimulate immigration of Jews into Palestine on a large scale, and as quickly as possible to settle Jewish immigrants upon the land through closer settlement and intensive cultivation of the soil.”

Faisal had conditioned his acceptance of the Balfour Declaration on the fulfillment of British wartime promises of independence to the Arabs. These were not kept.

Critics dismiss the Weizmann-Faisal agreement because it was never enacted; however, the fact that the leader of the Arab nationalist movement and the Zionist movement could reach an understanding is significant because it demonstrated that Jewish and Arab aspirations were not necessarily mutually exclusive.

Sources: Chaim Weizmann, Trial and Error, (NY: Schocken Books, 1966), pp. 246-247; Howard Sachar, A History of Israel: From the Rise of Zionism to Our Time, (NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1979), p. 121.

Pre-State Israel:

Pre-State Israel:

Feisal-Frankfurter Correspondence

(March 1919)

Pre-State Israel: Table of Contents | Jewish Immigration | Partition Plans

Letter from Emir Feisal (Son of Hussen Ibn Ali, Sharif of Mecca) to Felix Frankfurter, associate of Dr. Chaim Weizmann:

DELEGATION HEDJAZIENNE

Paris Peace Conference

March 3, 1919

Dear Mr. Frankfurter:

I want to take this opportunity of my first contact with American Zionists to tell you what I have often been able to say to Dr. Weizmann in Arabia and Europe.

We feel that the Arabs and Jews are cousins in having suffered similar oppressions at the hands of powers stronger than themselves, and by a happy coincidence have been able to take the first step towards the attainment of their national ideals together.

The Arabs, especially the educated among us, look with the deepest sympathy on the Zionist movement. Our deputation here in Paris is fully acquainted with the proposals submitted yesterday by the Zionist Organisation to the Peace Conference, and we regard them as moderate and proper. We will do our best, in so far as we are concerned, to help them through: we will wish the Jews a most hearty welcome home.

With the chiefs of your movement, especially with Dr. Weizmann, we have had and continue to have the closest relations. He has been a great helper of our cause, and I hope the Arabs may soon be in a position to make the Jews some return for their kindness. We are working together for a reformed and revived Near East, and our two movements complete one another. The Jewish movement is national and not imperialist. Our movement is national and not imperialist, and there is room in Syria for us both. Indeed I think that neither can be a real success without the other.

People less informed and less responsible than our leaders and yours, ignoring the need for cooperation of the Arabs and Zionists, have been trying to exploit the local difficulties that must necessarily arise in Palestine in the early stages of our movements. Some of them have, I am afraid, misrepresented your aims to the Arab peasantry, and our aims to the Jewish peasantry, with the result that interested parties have been able to make capital out of what they call our differences.

I wish to give you my firm conviction that these differences are not on questions of principle, but on matters of detail such as must inevitably occur in every contact of neighbouring peoples, and as are easily adjusted by mutual good will. Indeed nearly all of them will disappear with fuller knowledge.

I look forward, and my people with me look forward, to a future in which we will help you and you will help us, so that the countries in which we are mutually interested may once again take their places in the community of civilised peoples of the world.

Believe me,

Yours sincerely,

(Sgd.) Feisal

Letter of reply from Felix Frankfurter to Emir Feisal:

Paris Peace Conference

March 5, 1919

Royal Highness,

Allow me, on behalf of the Zionist Organisation, to acknowledge your recent letter with deep appreciation.

Those of us who come from the United States have already been gratified by the friendly relations and the active cooperation maintained between you and the Zionist leaders, particularly Dr. Weizmann. We knew it could not be otherwise; we knew that the aspirations of the Arab and the Jewish peoples were parallel, that each aspired to re-establish its nationality in its own homeland, each making its own distinctive contribution to civilisation, each seeking its own peaceful mode of life.

The Zionist leaders and the Jewish people for whom they speak have watched with satisfaction the spiritual vigour of the Arab movement. Themselves seeking justice, they are anxious that the just national aims of the Arab people be confirmed and safeguarded by the Peace Conference.

We knew from your acts and your past utterances that the Zionist movement -- in other words the national aim of the Jewish people -- had your support and the support of the Arab people for whom you speak. These aims are now before the Peace Conference as definite proposals by the Zionist Organisation. We are happy indeed that you consider these proposals “moderate and proper,” and that we have in you a staunch supporter for their realisation.

For both the Arab and the Jewish peoples there are difficulties ahead -- difficulties that challenge the united statesmanship of Arab and Jewish leaders. For it is no easy task to rebuild two great civilisations that have been suffering oppression and misrule for centuries. We each have our difficulties we shall work out as friends, friends who are animated by similar purposes, seeking a free and full development for the two neighbouring peoples. The Arabs and Jews are neighbours in territory; we cannot but live side by side as friends.

Very respectfully,

(Sgd.) Felix Frankfurter

Balfour Declaration:

U.S. Congress Endorses Declaration

(September 21, 1922)

Balfour Declaration: Table of Contents | Text of Declaration | Commentary

Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress Assembled.

That the United States of America favors the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which will prejudice the civil and religious rights of Christian and all other non-Jewish communities in Palestine, and that the holy places and religious buildings and sites in Palestine shall be adequately protected.

Sources: Public Resolution No. 73, 67th Congress, Second Session

Herbert Hoover Administration:

Balfour Declaration:

Anti-Semitism:

Israel:

Herbert Hoover Administration:

Statement Endorsing Balfour Declaration

(October 29, 1932)

Hoover Administration: Table of Contents | Relief Funding | Jewish Relief Campaign

Message from U.S. President Herbert Hoover addressed to Lewis L. Strauss and released by the Zionist Organization of America on the fifteenth anniversary of the Balfour Declaration

On the occasion of your celebration of the 15th Anniversary of the Balfour Declaration, which received the unanimous approval of both Houses of Congress by the adoption of the Lodge-Fish resolution in 1922, I wish to express the hope that the ideal of the establishment of the National Jewish Home in Palestine, as embodied in that Declaration, will continue to prosper for the good of all the people inhabiting the Holy Land.

I have watched with genuine admiration the steady and unmistakable Progress made in the rehabilitation of Palestine which, desolate for centuries, is now renewing its youth and vitality through the enthusiasm, hard work and self-sacrifice of the Jewish pioneers who toil there in a spirit of peace and social justice. It is very gratifying to note that many American Jews, Zionists as well as non-Zionists, have rendered such splendid service to this cause which merits the sympathy and moral encouragement of everyone.

Sources: Public Papers of the Presidents

Balfour Declaration:

U.S. President Roosevelt Endorses Declaration

(February 6, 1937)

Balfour Declaration: Table of Contents | Text of Declaration | Commentary

Greeting from U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt to the United Palestine Appeal addressed to Stephen S. Wise.

Dear Doctor Wise:Please convey my good wishes to the men and women gathering in Washington for the National Conference for Palestine which has been summoned by the United Palestine Appeal. The American people, ever zealous in the cause of human freedom, have watched with sympathetic interest the effort of the Jews to renew in Palestine the ties of their ancient homeland and to reestablish Jewish culture in the place where for centuries it flourished and whence it was carried to the far corners of the world.This year marks the twentieth anniversary of the Balfour Declaration, the keystone of contemporary reconstruction activities in the Jewish homeland. Those two decades have witnessed a remarkable exemplification of the vitality and vision of the Jewish pioneers in Palestine. It should be a source of pride to Jewish citizens of the United States that they, too, have had a share in this great work of revival and restoration. It gives me great pleasure to send all who are participating in your deliberations my hearty felicitations and warmest personal greetings.Very sincerely yours,Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Sources: Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States

Benjamin Disraeli

(1804 - 1881)

Benjamin Disraeli was born Jewish and is therefore sometimes considered Britain's first Jewish Prime Minister. In fact, he was a practicing Anglican. In 1813, his father's quarrel with the synagogue of Bevis Marks led to the decision in 1817 to have his children baptized as Christians (ironically, when Disraeli was 13 and eligible for Bar Mitzvah). Until 1858 Jews were excluded from Parliament; except for the father's decision Disraeli's political career could never have taken the form it did.

Benjamin Disraeli, was born in London on 21st December, 1804. His father, Isaac Disraeli, was the author of several books on literature and history, including The Life and Reign of Charles I (1828). After a private education Disraeli was trained as a solicitor.

Like his father, Isaac Disraeli, Benjamin took a keen interest in literature. His first novel, Vivian Grey was published in 1826. The book sold very well and was followed by The Young Duke (1831), Contarini Fleming (1832), Alroy (1833),Henrietta Temple (1837) and Venetia(1837).

Benjamin Disraeli was also interested in politics. In the early 1830s he stood in several elections as a Whig, Radical and as an Independent. Disraeli's early attempts ended in failure, but he was eventually elected to represent Maidstone in 1837.

Disraeli's maiden speech in the House of Commons was poorly received and after enduring a great deal of barracking ended with the words: "though I sit down now, the time will come when you will hear me." Disraeli was now a progressive Tory and advocated triennial parliaments and the secret ballot. He was sympathetic to the demands of the Chartists and in one speech argued that the "rights of labour were as sacred as the rights of property".

In 1839 Benjamin Disraeli married the extremely wealthy widow, Mrs. Wyndham Lewis. The marriage was a great success. On one occasion Disraeli remarked that he had married for money, and his wife replied, "Ah! but if you had to do it again, you would do it for love."

After the Conservative victory in the 1841 General Election, Disraeli suggested to Sir Robert Peel, the new Prime Minister, that he would make a good government minister. Peel disagreed and Disraeli had to remain on the backbenches. Disraeli was hurt by Peel's rejection and over the next few years he became a harsh critic of the Conservative government.

In 1842 Disraeli helped to form the Young England group. Disraeli and members of his group argued that the middle class now had too much political power and advocated an alliance between the aristocracy and the working class. Disraeli suggested that the aristocracy should use their power to help protect the poor. This political philosophy was expressed in Disraeli's novels Coningsby (1844), Sybil (1845) and Tancred (1847). In these books the leading characters show concern about poverty and the injustice of the parliamentary system. Disraeli favoured a policy of protectionism and strongly opposed Peel's decision to repeal the Corn Laws. This issue split the Conservative Party and Disraeli's attacks on Peel helped to bring about his political downfall.

In 1852 Lord John Russell, the leader of the Whig government, resigned. Lord Derby, the new Prime Minister, appointed Disraeli as his Chancellor of the Exchequer. This period of power only lasted a few months and Derby was soon replaced by the Earl of Aberdeen.

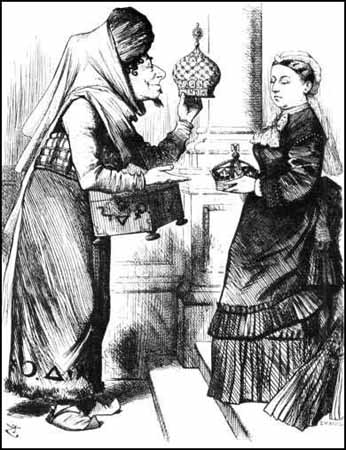

John Tenniel, Disraeli and Queen Victoria Exchanging Gifts(Punch Magazine, 1876) |

Lord Derby became Prime Minister again in 1858 and once again Disraeli was appointed as Chancellor of the Exchequer. He also became leader of the House of Commons and was responsible for the introduction of measures to reform parliament. In February, 1858, Disraeli proposed the equalization of the town and county franchise. This would have resulted in some men in towns losing the vote and was opposed by the Liberals. An amendment proposed by Lord John Russell "condemning this disfranchisement" was passed by 330 to 291.

In 1859 Lord Palmerston, became Prime Minister, and Disraeli once more lost his position in the government. For the next seven years the Liberals were in power and it was not until 1866 that Disraeli returned to the cabinet. Once again, Lord Derby appointed Disraeli as his Chancellor of the Exchequer and leader of the House of Commons.

Some members of the Liberal Party, including the new leader, William Gladstone, had been in favour of legislation that would have extended the franchise. His attempts to obtain parliamentary reform failed but Disraeli was convinced that if the Liberals returned to power, Gladstone was certain to try again. Benjamin Disraeli argued that the Conservatives were in danger of being seen as an anti-reform party. In 1867 Disraeli proposed a new Reform Act. Lord Cranborne (later the Marquis of Salisbury) resigned in protest against this extension of democracy.

In the House of Commons, Disraeli's proposals were supported by Gladstone and his followers and the measure was passed. The 1867 Reform Act gave the vote to every male adult householder living in a borough constituency. Male lodgers paying £10 for unfurnished rooms were also granted the vote. This gave the vote to about 1,500,000 men.

The Reform Act also dealt with constituencies and boroughs with less than 10,000 inhabitants lost one of their MPs. The forty-five seats left available were distributed by: (i) giving fifteen to towns which had never had an MP; (ii) giving one extra seat to some larger towns - Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham and Leeds; (iii) creating a seat for the University of London; (iv) giving twenty-five seats to counties whose population had increased since 1832.

In 1868 Lord Derby resigned and Benjamin Disraeli became the new Prime Minister. However, in the 1868 General Election that followed, William Gladstone and the Liberals were returned to power with a majority of 170.

After six years in opposition, Disraeli and the Conservative Party won the 1874 General Election. It was the first time since 1841 that the Tories in the House of Commons had a clear majority. Disraeli now had the opportunity to the develop the ideas that he had expressed when he was leader of the Young England group in the 1840s. Social reforms passed by the Disraeli government included: the Artisans Dwellings Act (1875), the Public Health Act (1875), the Pure Food and Drugs Act (1875), the Climbing Boys Act (1875), the Education Act (1876).

Disraeli also introduced measures to protect workers such as the 1874 Factory Act and the Climbing Boys Act (1875). Disraeli also kept his promise to improve the legal position of trade unions. The Conspiracy and Protection of Property Act (1875) allowed peaceful picketing and the Employers and Workmen Act (1878) enabled workers to sue employers in the civil courts if they broke legally agreed contracts.

Unlike William Gladstone, Disraeli got on very well with Queen Victoria. She approved of Disraeli's imperialist views and his desire to make Britain the most powerful nation in the world. In 1876 Victoria agreed to his suggestion that she should accept the title of Empress of India.

In August 1876 Queen Victoria granted Disraeli the title Lord Beaconsfield. Disraeli now left the House of Commons but continued as Prime Minister and now used the House of Lords to explain his government's policies. At the Congress of Berlin in 1878 Disraeli gained great acclaim for his success in limiting Russia's power in the Balkans.

The Liberals defeated the Conservatives in the 1880 General Election and after William Gladstone became Prime Minister, Disraeli decided to retire from politics. Disraeli hoped to spend his retirement writing novels but soon after the publication of Endymion (1880) he became very ill. Benjamin Disraeli died on 19th April, 1881.

Sources: Spartacus Educational; Britannica.com

Walter Rothschild, 2nd Baron Rothschild (1868 - 1937)Walter Rothschild, 2nd Baron Rothschild, a scion of the Rothschild family, was a British banker, politician, and zoologist. |

Walter Rothschild was born in London, the eldest son and heir of Lord [Nathan] Rothschild, an immensely wealthy financier, of the international Rothschild financial dynasty, and the first Jewish peer in England.The eldest of three children, Walter was deemed to have delicate health and was educated at home. As a young man he traveled in Europe, attending the university at Bonn for a year before entering Magdalene College atCambridge. In 1889, leaving Cambridge after two years, he was required to go into the family banking business to study finance.At the age of seven, he declared that he would run a zoological museum. As a child, he collected insects, butterflies, and other animals. Among his pets at the family home in Tring Park were kangaroos and exotic birds. As a boy, Rothschild was once dragged off his horse and assaulted by workmen while on a hunting ride near Tring, an experience that he personally attributed to Anti-Semitism.At 21, he reluctantly went to work at the family bank, N M Rothschild & Sons in London. He worked there from 1889 to 1908. Нe evidently lacked any interest or ability in the financial profession, but it was not until 1908 that he was finally allowed to give it up. However, his parents established a zoological museum as a compensation, and footed the bill for expeditions all over the world to seek out animals. At one point he had his photograph taken riding on a giant tortoise and, on another occasion, drove a carriage harnessed to six zebras to Buckingham Palace to prove that zebras could be tamed.Rothschild was 6' 3" tall, suffered from a speech impediment and was very shy. Though he never married, Rothschild had two mistresses, one of whom bore him a daughter.Walter Rothschild was a Conservative Member of Parliament for Aylesbury from 1899 until he retired from politics in January 1910.Despite his health, Rothschild served part-time as an officer in a Territorial Army unit, the Royal Buckinghamshire Yeomanry, being promoted Major in 1903 and retiring in 1909.As an active Zionist and close friend of Chaim Weizmann, he worked to formulate the draft declaration for a Jewish homeland in Palestine. On 2 November 1917 he received a letter from the British foreign secretary,Arthur Balfour, addressed to his London home at 148 Piccadilly. In this letter the British government declared its support for the establishment in Palestine of "a national home for the Jewish people". This letter became known as the Balfour Declaration.

Sources: WikipediaWikimedia, By Helgen KM, Portela Miguez R, Kohen J, Helgen L [CC BY 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Anti-Semitism:

Mantagu Memo on the Anti-Semitism of the British Government

(August 23, 1917)

Anti-Semitism: Table of Contents | European Anti-Semitism in 2013 | Wilhelm Marr

Memorandum of Edwin Montagu on the Anti-Semitism of the Present (British) Government - Submitted to the British Cabinet, August 1917

I have chosen the above title for this memorandum, not in any hostile sense, not by any means as quarrelling with an anti-Semitic view which may be held by my colleagues, not with a desire to deny that anti-Semitism can be held by rational men, not even with a view to suggesting that the Government is deliberately anti-Semitic; but I wish to place on record my view that the policy of His Majesty's Government is anti-Semitic in result will prove a rallying ground for Anti-Semites in every country in the world.

This view is prompted by the receipt yesterday of a correspondence between Lord Rothschild and Mr. Balfour.Lord Rothschild's letter is dated the 18th July and Mr. Balfour's answer is to be dated August 1917. I fear that my protest comes too late, and it may well be that the Government were practically committed when Lord Rothschild wrote and before I became a member of the Government, for there has obviously been some correspondence or conversation before this letter. But I do feel that as the one Jewish Minister in the Government I may be allowed by my colleagues an opportunity of expressing views which may be peculiar to myself, but which I hold very strongly and which I must ask permission to express when opportunity affords.I believe most firmly that this war has been a death-blow to Internationalism, and that it has proved an opportunity for a renewal of the slackening sense of Nationality, for it is has not only been tacitly agreed by most statesmen in most countries that the redistribution of territory resulting from the war should be more or less on national grounds, but we have learned to realise that our country stands for principles, for aims, for civilisation which no other country stands for in the same degree, and that in the future, whatever may have been the case in the past, we must live and fight in peace and in war for those aims and aspirations, and so equip and regulate our lives and industries as to be ready whenever and if ever we are challenged. To take one instance, the science of Political Economy, which in its purity knows no Nationalism, will hereafter be tempered and viewed in the light of this national need of defence and security. The war has indeed justified patriotism as the prime motive of political thought.It is in this atmosphere that the Government proposes to endorse the formation of a new nation with a new home in Palestine. This nation will presumably be formed of Jewish Russians, Jewish Englishmen, Jewish Roumanians, Jewish Bulgarians, and Jewish citizens of all nations - survivors or relations of those who have fought or laid down their lives for the different countries which I have mentioned, at a time when the three years that they have lived through have united their outlook and thought more closely than ever with the countries of which they are citizens.Zionism has always seemed to me to be a mischievous political creed, untenable by any patriotic citizen of the United Kingdom. If a Jewish Englishman sets his eyes on the Mount of Olives and longs for the day when he will shake British soil from his shoes and go back to agricultural pursuits in Palestine, he has always seemed to me to have acknowledged aims inconsistent with British citizenship and to have admitted that he is unfit for a share in public life in Great Britain, or to be treated as an Englishman. I have always understood that those who indulged in this creed were largely animated by the restrictions upon and refusal of liberty to Jews in Russia. But at the very time when these Jews have been acknowledged as Jewish Russians and given all liberties, it seems to be inconceivable that Zionism should be officially recognised by the British Government, and that Mr. Balfour should be authorized to say that Palestine was to be reconstituted as the "national home of the Jewish people". I do not know what this involves, but I assume that it means that Mahommedans and Christians are to make way for the Jews and that the Jews should be put in all positions of preference and should be peculiarly associated with Palestine in the same way that England is with the English or France with the French, that Turks and other Mahommedans in Palestine will be regarded as foreigners, just in the same way as Jews will hereafter be treated as foreigners in every country but Palestine. Perhaps also citizenship must be granted only as a result of a religious test.I lay down with emphasis four principles:

Herbert Louis Samuel

(1870 - 1963)

When the first high commissioner for Palestine arrived in Jerusalem, he was met with a seventeen-gun salute and endless words of welcome. Sir Herbert Samuel made the journey in June 1920, and served as high commissioner for a period of five years. His appointment was viewed by many Jews as affirmation that the British promise for a Jewish National Home in Palestine would be honored. The telegram sent to the Zionist Organisation Central Office in London reflects the atmosphere of excitement that surrounded Samuel's arrival.

Samuel himself was moved by the outpouring of emotion which greeted him in the Land of Israel. He had been raised in an Orthodox Jewish home, and although he subsequently ceased practicing, he remained intensely interested in Jewish communal problems.

Samuel's career in different British posts was unique in its scope; he was the first unconverted Jew to serve in a Cabinet office.

Samuel first presented the idea of a British protectorate in 1915. In a memorandum to Prime Minister Asquith, he proposed that a British protectorate be established which would allow for increased Jewish settlement. In time, the future Jewish majority would enjoy a considerable degree of autonomy. Herbert believed that the creation of a Jewish center would flourish spiritually and intellectually, resulting in the character improvement of Jews all over the world. At that time, however, Prime Minister Asquith was not interested in pursuing such an option, and no action was taken. Yet significant groundwork had been accomplished, and it was on the basis of Samuel's work that the Balfour Declaration was later written.

It was therefore no surprise that Samuel was appointed first high commissioner of Palestine. His appointment made him the first Jew to govern in the Land of Israel in 2,000 years. Anxious to serve his country well, Samuel made it clear that his policy was to unite all dissenting groups under the British flag. Attempting to appease the Arabs in Palestine, Samuel made several significant concessions. It was he who appointed Hajj Amin al-Husseini, a noted Arab nationalist extremist, to be Mufti of Jerusalem. In addition, he slowed the pace of Jewish immigration to Palestine, much to the distress of the Zionists. In attempting to prove his impartiality, the Zionists claimed that he had gone too far, and had damaged the Zionist cause. Many Zionists were ultimately disappointed by Samuel, who they felt did not live up to the high expectations they had of him.

Sources: The Jewish Agency for Israel and The World Zionist Organization

Pre-State Israel:

Pre-State Israel:

The Sykes-Picot Agreement

(1916)

Pre-State Israel: Table of Contents | Balfour Declaration | Peel Commission

The Sykes-Picot Agreement (officially the 1916 Asia Minor Agreement) was a secret agreement reached during World War I between the British and French governments pertaining to the partition of the Ottoman Empire among the Allied Powers. Russia was also privy to the discussions.

Click to Enlarge:

The Middle East per the Sykes-Picot Agreement. |

The first round of discussions took place in London on November 23, 1915 with the French government represented by François-Georges Picot, a professional diplomat with extensive experience in the Levant, and the British delegation led by Sir Arthur Nicolson. The second round of discussions took place December 21 with the British now represented by Sir Mark Sykes, a leading expert on the East.

Having juxtaposed the desiderata of all the parties concerned - namely the British, the French and the Arabs - the two statesmen worked out a compromise solution. The terms of the partition agreement were specified in a letter dated May 9, 1916, which Paul Cambon, French ambassador in London, addressed to Sir Edward Grey, British foreign secretary. These terms were ratified in a return letter from Grey to Cambon on May 16 and the agreement became official in an exchange of notes among the three Allied Powers on April 26 and May 23, 1916.

According to the agreement, France was to exercise direct control over Cilicia, the coastal strip of Syria, Lebanon and the greater part of Galilee, up to the line stretching from north of Acre to the northwest corner of the Sea of Galilee ("Blue Zone"). Eastward, in the Syrian hinterland, an Arab state was to be created under French protection ("Area A"). Britain was to exercise control over southern Mesopotamia ("Red Zone"), as well as the territory around the Acre-Haifa bay in the Mediterranean with rights to build a railway from there to Baghdad. The territory east of the Jordan River and the Negev desert, south of the line stretching from Gaza to the Dead Sea, was allocated to an Arab state under British protection ("Area B"). South of France's "blue zone," in the area covering the Sanjak of Jerusalem and extending southwards toward the line running approximately from Gaza to the Dead Sea, was to be under international administration ("Brown Zone").

In the years that followed, the Sykes-Picot Agreement became the target of bitter criticism both in France and in England. Lloyd George referred to it as an "egregious" and a "foolish" document. Zionist aspirations were also passed over and this lapse was severely criticized by William R. Hall, head of the Intelligence Department of the British Admiralty, who pointed out that the Jews have "a strong material, and a very strong political interest in the future of the country and that in the Brown area the question of Zionism… [ought] to be considered."

Click to Enlarge:

Areas of Palestine per the agreement |

The agreement was officially abrogated by the Allies at the San Remo Conference in April 1920, when the Mandate for Palestine was conferred upon Britain.

Text of Sykes-Picot Agreement

It is accordingly understood between the French and British governments:That France and Great Britain are prepared to recognize and protect an independent Arab states or a confederation of Arab states (a) and (b) marked on the annexed map, under the suzerainty of an Arab chief. That in area (a) France, and in area (b) great Britain, shall have priority of right of enterprise and local loans. That in area (a) France, and in area (b) great Britain, shall alone supply advisers or foreign functionaries at the request of the Arab state or confederation of Arab states.That in the blue area France, and in the red area great Britain, shall be allowed to establish such direct or indirect administration or control as they desire and as they may think fit to arrange with the Arab state or confederation of Arab states.That in the brown area there shall be established an international administration, the form of which is to be decided upon after consultation with Russia, and subsequently in consultation with the other allies, and the representatives of the Shariff of Mecca.That great Britain be accorded (1) the ports of Haifa and acre, (2) guarantee of a given supply of water from the Tigres and Euphrates in area (a) for area (b). His majesty's government, on their part, undertake that they will at no time enter into negotiations for the cession of Cyprus to any third power without the previous consent of the French government.That Alexandretta shall be a free port as regards the trade of the British empire, and that there shall be no discrimination in port charges or facilities as regards British shipping and British goods; that there shall be freedom of transit for British goods through Alexandretta and by railway through the blue area, or (b) area, or area (a); and there shall be no discrimination, direct or indirect, against British goods on any railway or against British goods or ships at any port serving the areas mentioned.That Haifa shall be a free port as regards the trade of France, her dominions and protectorates, and there shall be no discrimination in port charges or facilities as regards French shipping and French goods. There shall be freedom of transit for French goods through Haifa and by the British railway through the brown area, whether those goods are intended for or originate in the blue area, area (a), or area (b), and there shall be no discrimination, direct or indirect, against french goods on any railway, or against french goods or ships at any port serving the areas mentioned.That in area (a) the Baghdad railway shall not be extended southwards beyond Mosul, and in area (b) northwards beyond Samarra, until a railway connecting Baghdad and Aleppo via the Euphrates valley has been completed, and then only with the concurrence of the two governments.That great Britain has the right to build, administer, and be sole owner of a railway connecting Haifa with area (b), and shall have a perpetual right to transport troops along such a line at all times. It is to be understood by both governments that this railway is to facilitate the connection of Baghdad with Haifa by rail, and it is further understood that, if the engineering difficulties and expense entailed by keeping this connecting line in the brown area only make the project unfeasible, that the french government shall be prepared to consider that the line in question may also traverse the Polgon Banias Keis Marib Salkhad tell Otsda Mesmie before reaching area (b).For a period of twenty years the existing Turkish customs tariff shall remain in force throughout the whole of the blue and red areas, as well as in areas (a) and (b), and no increase in the rates of duty or conversions from ad valorem to specific rates shall be made except by agreement between the two powers.There shall be no interior customs barriers between any of the above mentioned areas. The customs duties leviable on goods destined for the interior shall be collected at the port of entry and handed over to the administration of the area of destination.It shall be agreed that the french government will at no time enter into any negotiations for the cession of their rights and will not cede such rights in the blue area to any third power, except the Arab state or confederation of Arab states, without the previous agreement of his majesty's government, who, on their part, will give a similar undertaking to the french government regarding the red area.The British and French government, as the protectors of the Arab state, shall agree that they will not themselves acquire and will not consent to a third power acquiring territorial possessions in the Arabian peninsula, nor consent to a third power installing a naval base either on the east coast, or on the islands, of the red sea. This, however, shall not prevent such adjustment of the Aden frontier as may be necessary in consequence of recent Turkish aggression.The negotiations with the Arabs as to the boundaries of the Arab states shall be continued through the same channel as heretofore on behalf of the two powers.It is agreed that measures to control the importation of arms into the Arab territories will be considered by the two governments.I have further the honor to state that, in order to make the agreement complete, his majesty's government are proposing to the Russian government to exchange notes analogous to those exchanged by the latter and your excellency's government on the 26th April last. Copies of these notes will be communicated to your excellency as soon as exchanged. I would also venture to remind your excellency that the conclusion of the present agreement raises, for practical consideration, the question of claims of Italy to a share in any partition or rearrangement of turkey in Asia, as formulated in Article 9 of the agreement of the 26th April, 1915, between Italy and the allies.His Majesty's Government further consider that the Japanese government should be informed of the arrangements now concluded.

Sources:Encyclopaedia Judaica. © 2008 The Gale Group. All Rights Reserved.

The Avalon Project and Middle East Maps [the maps are not in the original document]

L. Stein, The Balfour Declaration (1961), 237–69, index; E. Kedourie, England and the Middle East (1956), 29–66, 102–41; J. Nevakivi, Britain, France and the Arab Middle East (1969), 35–44, index; C. Sykes, Two Studies in Virtue (1953), index; H.F. Frischwasser-Ra'ana, The Frontiers of a Nation (1955), 5–73; I. Friedman, The Question of Palestine, 1914 – 1918. British-Jewish-Arab Relations (1973, 19922), 97–118; idem,Palestine: A Twice Promised Land? The British, the Arabs and Zionism, 1915 – 1920 (2000), 47–60.

The Avalon Project and Middle East Maps [the maps are not in the original document]

L. Stein, The Balfour Declaration (1961), 237–69, index; E. Kedourie, England and the Middle East (1956), 29–66, 102–41; J. Nevakivi, Britain, France and the Arab Middle East (1969), 35–44, index; C. Sykes, Two Studies in Virtue (1953), index; H.F. Frischwasser-Ra'ana, The Frontiers of a Nation (1955), 5–73; I. Friedman, The Question of Palestine, 1914 – 1918. British-Jewish-Arab Relations (1973, 19922), 97–118; idem,Palestine: A Twice Promised Land? The British, the Arabs and Zionism, 1915 – 1920 (2000), 47–60.

Israel:

Zionism

Israel: Table of Contents | Archaeology | Government & Politics

What is Zionsim?Literature on Zionsim

Pre-State Zionism

Anti-Zionism | Prominent Zionist Figures

Types of Zionism

Zionist Organizations Worldwide |

No comments:

Post a Comment